Revised: January 2019

By Sarah Owens and Michael Livingston

The great thing about our current economic system is that there is nothing so odious that it cannot become a legitimate source of income for someone. War, addiction, anthropomorphic climate change, extreme poverty, even homelessness.

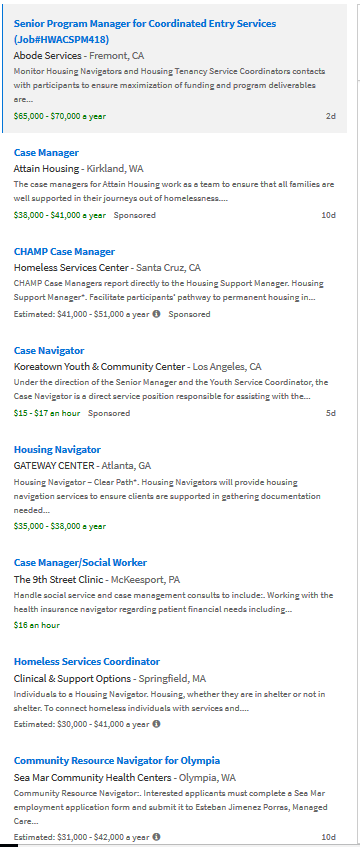

Used to be, if a person wanted to work with people experiencing homelessness, s/he had to become a member of the clergy, or work unpaid. Then, starting in the 80s and 90s, a person might find a low-paying position with a non-profit dedicated to that kind of work. Nowadays, though, it's possible not only to find a job at decent pay, but to make a career out of it.

How's that for progress?

All bitterness aside, the fact that today, especially in urban areas like Salem-Keizer, we've now got all these relative experts -- well, that's actually a good thing. These people are program managers, case managers, system navigators, case navigators, housing navigators, screeners, housing stability coordinators, coordinated entry specialists, housing specialists, housing services coordinators, support specialists, peer support specialists and service integration coordinators. And that's not even all.

What has changed?

Society has advanced to the point where homelessness and living at risk of homelessness is recognized as a condition, something akin to a wound or pneumonia or diabetes, that can be most effectively treated using a widely-framed medical model in a system of integrated care.

Please note the qualifier "widely-framed"

before registering outraged disagreement about

the effectiveness of the medical model in the comments section. We are

not talking about

the model's earliest iteration, which tended to take a mechanistic view of the individual as the sum of his curable diseases, while ignoring his state of mind, history of trauma, family and environment.

This enlightened medical model recognizes that people don't always act sensibly, and might from time to time need help making better choices. Choices like eating or drinking or smoking less, exercising more, etc., are obvious examples. Less obvious examples might be showering regularly or sleeping indoors or taking prescribed medication despite negative side effects.

Over time, research has shown what most people already know from personal experience -- i.e, that unconditional help in the form of information, encouragement, and opportunity are what move a person toward healthier choices, not fear, humiliation, isolation, rejection, insult or pity, which are the daily diet of the chronically homeless.

The gradual response to this awareness in the professional community has been toward integrated programs of care designed to provide the former and avoid, insofar as is humanly possible, reproducing the latter. These newly-designed programs require trained workers in a variety of positions, hence the new employment opportunities for those wanting to work with people experiencing homelessness.

So, you may be wondering, why is it downtown businesses can't contact one of these trained workers, instead of the police, when they need help dealing with incivilities and disruptive behavior? That's a good question.

One reason is that they don't know whom to contact, besides the police. As

Olivia's owner and

Downtown Homeless Solutions Task Force member, Sandy Powell, said at the first task force meeting, "I don't think we really know what resources are available, and how we can help...It'd be nice if we knew those resources...if my employees knew what to do."

Another reason is that the local continuum of care has significant gaps, a major one being "street outreach" workers. These are workers whose primary aim is to bring people off the streets and get them connected to services. (Aka "engaged in" services, a euphemism for when a person has managed to overcome shame and abject hopelessness sufficiently to face the prospect of further shame and disappointment as they try to better their situation.) Whether a person engages in services has a great deal to do with what sort of services are available. In Salem, services for some populations are severely limited, especially the chronically homeless, who tend to live downtown. So, street outreach workers downtown might sometimes have to function as street "case managers", checking in on folks, seeing where they are on MWVCAA's housing wait list, advocating for them, etc.

The Union Gospel Mission has what it calls a "Search & Rescue Team" that travels around to the camps, but it's pretty informal. Northwest Human Services' HOST program does some limited "street outreach", but it's oriented toward youth. Maybe, probably, if they were asked to, local providers could pull together an outreach program so businesses had someone besides the police to call, especially if local businesses would help to support such a program financially. But, as far as we know, no one has asked them to do that. So, instead, businesses call the police, who are trained on law enforcement, not on working with the homeless.

The arrangement really doesn't make much sense, and the police know it. As Ronal Serpas, a former police chief put it,

A lot of America has empathy for people, but they don't have a lot of patience. So the question becomes, "I want you to remove these people from in front of my business. I want you to remove these people from in front of the park where I bring my children. I want you to remove these people from in front of my home. And, when they commit incivilities that are also violations of the law, I expect you to do something about it."

One of our sergeants was interviewed on television, and it stunned me when he said it, and it remains with me to this day. He said to the television news reporter, who was potentially putting him in the box of, "You must really get off on arresting these people." And he said, "Ma'am, let me be perfectly clear with you." He said, "I am giving people a life sentence, two days at a time, and I hate it. It's not what I signed up for. It's not why I became a police officer. But in our community, the only alternative we have for these many events, [is] to bring people to jail. They go to jail, two days later, they recover enough to be back out on the street, and then I see them again on day four."

Now, that is absolutely what is going on in America...Officers don't have anything but the back of their car, and that is a solution for no one.

Ron Bruno, a law enforcement official who developed a crisis response team for Salt Lake County, Utah, has observed that the vast majority of 911 calls concerning someone experiencing a mental health crisis do

not require law enforcement. He asks, "So why do we keep opening that door? Because every time law enforcement shows up on the scene, you are bringing the justice system."

One solution would be to train teams of law enforcement officials to the point that they become experts on the resources in the community and partners with providers, so that they become, in effect, outreach workers. That's

kind of what's been done with the Downtown Enforcement Team, but is this really the best way to go?

It wouldn't seem so. As Miriam Krinsky observed, "Our criminal justice system is filling a space that our mental health and public health systems need to be filling." She suggests that the more the criminal justice system does to fill that space, even if they do it imperfectly, the less likely it is that the mental and public health sectors will step up. Doesn't it make more sense to ask the mental and public health sectors to step up? For the City (and the County) to figure out what would that take, and help make that happen?

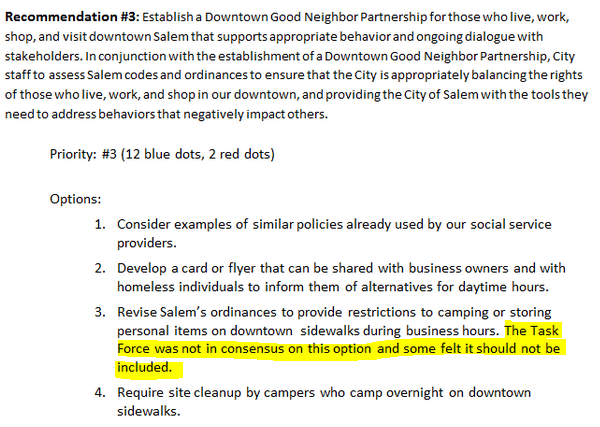

The sixth and supposedly final meeting of the Downtown Homeless Solutions Task Force has been scheduled for August 1. At one point, the purpose of this meeting was to receive the results of staff research, which the task force was then going to use to formulate recommendations.

Now, however, it appears recommendations will be "presented", and the task force will then discuss them.

Presumably, the recommendations will be detailed versions of what was discussed at the public hearing on June 13. Toilets, sanitation, a contact list, showers/laundry, behavior expectations, tougher laws, work.

It's doubtful, but not impossible, we will see in connection with item c, a recommendation to direct staff to work with local providers in developing an outreach program or team, so businesses have someone besides the police to call when they encounter disruptive behavior, and to work with local businesses on how they might support such a program financially.

More likely, however, the item c recommendation will be just what's indicated in the June 13 agenda -- a list of numbers from the

2-1-1 website, which the business owner or employee won't have the knowledge or expertise to navigate, and will cause him or her to become even more frustrated before s/he finally ends up calling the police, even though the situation doesn't require law enforcement.

Item f will doubtless remain a recommendation, and remain vague, because, although everyone pretty much knows that law enforcement isn't a good response to homelessness, we also don't have much else. Including patience.