By Sarah Owens and Michael Livingston

April saw heavy rains, flooding, refuse from camps being swept into the Willamette, premature death, rent rises, budget cuts and little good news on the ground in what some call the fight to bring a functional end to homelessness in Oregon.

See Bach, J. "

Salem apartment rents continue to rise, but Oregon housing crunch shows signs of easing." (3 April 2019,

Statesman Journal.) Urness, Z. "

Heavy rainfall expected to bring flooding and evacuations across Western Oregon." (7 April 2019,

Statesman Journal.) Barreda, V. "

50-year old homeless man dies of natural causes at Wallace Marine Park." (7 April 2019,

Statesman Journal.) Bach, J. "

Piles of trash along Salem's Willamette Slough spur concerns, cleanup program starts in May." 8 April 2019,

Statesman Journal.) Brynelson, T. "

City manager proposes budget cuts to homeless aid, youth programs to help general fund." (19 April 2019,

Salem Reporter.)

While the

Statesman Journal said the "cleanup program starts in May", Jimmy Jones, Executive Director of the Mid Willamette Valley Community Action Agency emailed us last week that the private property north of Wallace Marine Park was being posted "no trespassing" and that "whatever survived the flood will be bulldozed." He added, "it’s hard to say exactly what impact that will have on the downtown. We are expecting a few really difficult service days." See Bach, J. "

Salem area homeless told to move from Wallace Marine Park area." (1 May 2019,

Statesman Journal.)

Not the best time for the community to hear that the City plans to halve the challenging, but successful, Homeless Rental Assistance Program (HRAP), which targets the chronically homeless population. But, the problem's more nuanced than it's been presented, as Lynelle Wilcox discovered at the budget committee meeting on April 23, where she offered comment in support of continued and full funding for the warming centers and HRAP.

In response to questions raised by her comments, Urban Development Director (UDD) Kristin Retherford explained, in essence, that the limiting factors for the program had been the limited supply of landlords willing to work with the chronically homeless, and the need to maintain the recommended caseload. As a consequence, HRAP had so far not cost the City more than $700K/year, and unspent allocations had been carried over. See Brynelson, T. "

City manager proposes budget cuts to homeless aid, youth programs to help general fund." (19 April 2019,

Salem Reporter.) Thus, the proposed budget is more of a realignment with capacity than a cut.

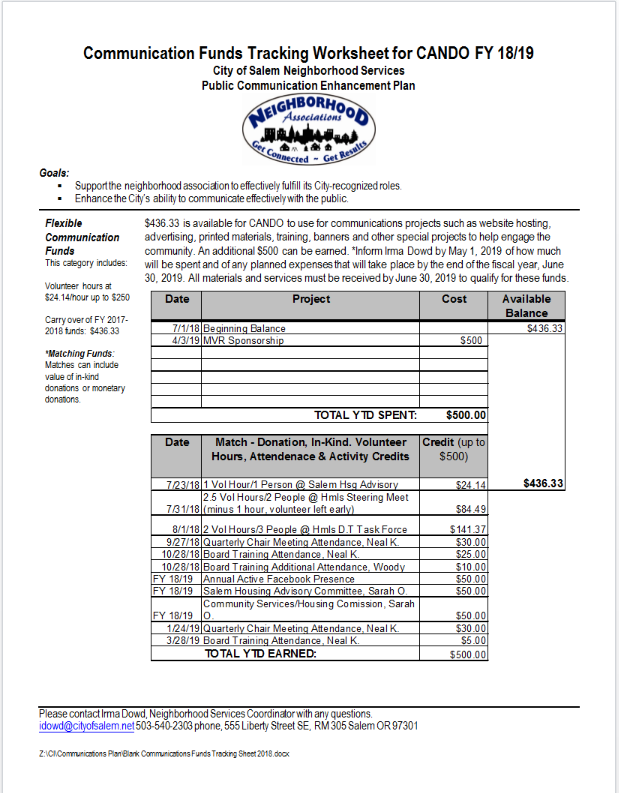

According to what Retherford told the committee, HRAP has, to date, placed 153 in housing, with an attrition rate of about 20% due to eviction, death and changed personal circumstances. Fifty-one had "graduated" and moved onto Housing Choice Vouchers. The program queue consists of 3 basic categories: 45 are "enrolled" (working with case managers to remove various barriers to a housing placement); 15 have been referred and are waiting to be enrolled; and another 200 have been assessed as high needs and are waiting to be referred to the program. There are not enough housing units or case managers for those in that last category. (City funds do not cover all case manager salaries. For example, one position is covered by a two-year grant from the Meyer Memorial Trust.)

|

| Proposed 2019-2020 Budget, Book 1, p. 4 |

Wilcox was back at the May 1 budget committee meeting to urge the City to keep the current $1.4M budget and use the additional funds to add program capacity and relieve the bottleneck. But, if the City were to do that, they risk not having sufficient funds for barrier removal and rent assistance, because so many of those resources went toward adding capacity.

So, HRAP just isn't

scalable in the current housing market, at least not without a lot more resources, and the housing authority is wise not to try to expand beyond what they believe they can handle. The fact is, it took Salem decades to grow its chronically homeless population to a size that's twice the national average, and it's going to take time to bring those numbers down.

That said,

last year's budget states that a "sustainability plan" for HRAP would be developed "in FY 2019" for City Council consideration and would include "realistic choices, some difficult, to maintain HRAP into the future." No mention of said plan at the 4/24 or 5/1 budget committee meetings.

Nor was there any mention of the Good Neighbor Partnership, which also would target the chronically homeless, specifically, those living downtown. Could it be that downtown business owners aren't complaining? See "

Bureaucratic BS Buries Good Neighbor Partnership."

Member-Mayor Bennett got the last word on HRAP, reminding everyone that HRAP was just

one of the City/SHA's housing programs (see

here for a list of SHA's current housing preservation projects including the Rental Assistance Demonstration project, which attempts to compensate for the federal government's refusal to provide stable funding for maintenance and repair, Redwood Crossings [formerly Fisher Road], Southfair Apartments and Yaquina Hall), and promising to go after some of that $100M reportedly being spent on "

services tied to homelessness." See Brynelson, T. "

Report: Region spent $100 million last year on services tied to homelessness." (8 April 2019,

Salem Reporter.) Good luck with that, Mayor.

Stably housing the chronically homeless is relatively do-able. It's the future that should concern us, according to a new ECO Northwest report on homelessness in Oregon.

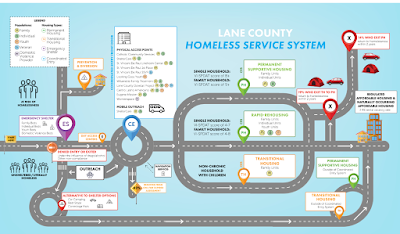

Oregon’s policy discussion might improve if homelessness were described as two, related crises. One crisis affects a population of individuals with highly challenging personal circumstances who will struggle to remain housed absent sustained, intensive support. A second crisis affects more than 150,000 households: the short-term homeless plus the growing numbers of severely cost-burdened renters on the verge of homelessness. The first crisis, while challenging, is within the scope of traditional, local homeless agencies to address and solve with additional resources and efficiencies. The second crisis is not. Meaningful progress there would require action by a much broader set of public, private, local, state, and federal actors. See Tapogna, J. & Baron, M. "Homelessness in Oregon, A Review of Trends, Causes and Policy Options." (13 March 2019, Oregon Community Foundation.)

We asked Jimmy Jones what he had to say about the report. He wrote:

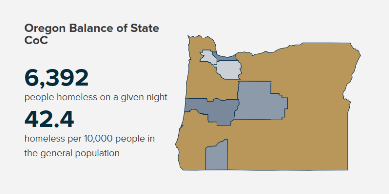

Oregon suffers from a double bind, having an extraordinary large unsheltered homeless population [14,476 per the 2018 Point-in-Time homeless count] and very little operable information on the nature of that homeless populations. There is also next to no analytical information on the size, vulnerabilities, and composition of the Oregon homeless population as a whole. This new study helps, but it too underestimates the scope of the problem. Though warning us about the unreliability of PIT count information, it goes on to base most of its observations on that same information. The infrastructure in rural America is eroding. Our next big wave of homelessness will be in rural camps spread across backwoods and frontier counties throughout the west. PIT counts stand little chance of ever accurately capturing a rural homeless population. Still, the report has promise and value because it is one of the few analytical discussions of the homeless crisis in Oregon. The only other state body that gathers research to inform public policy on homelessness is Oregon Housing and Community Services, and generally they do not often publish these kinds of analytical public reports.

One of the things the report does well is to understand that there are many different homeless populations in Oregon. The affordable housing crisis is triggering a considerable percentage of that recent wave of homelessness. But those who become homeless for primarily economic reasons tend not to stay homeless long. They generally self-resolve.

The report does note that unsheltered and chronic rates are very high and growing, but it does not make the connection that this population--despite the public's general assumption that the street homeless are the first served -- is not a priority in the state funding model. The only funding source that prioritizes unsheltered chronic homeless in Oregon are the HUD COC programs. In Oregon, 28 of the 36 counties are served by the Rural Oregon Continuum of Care. The ROCC has one of the largest total homeless populations in the United States, and ought to draw a total HUD grant somewhere in the range of $12-15 million. Instead, because of the ROCC's sheer size, performance issues, and the failure to collaborate and collectively plan, it has a federal grant only a little north of $3 million. The ROCC has what is probably the single most inadequate federal grant in the United States, given a homeless population of this size.

The report does note that there are many structural challenges to ending homelessness in Oregon that have nothing to do with the homeless population. Housing construction is too expensive, too slow, and mired in extraordinary bureaucratic barriers. Housing Authorities have the means to make a serious dent in homelessness, but have never prioritized access for homeless clients, and when they have they have historically not acted in a collaborative manner, refusing to use the region's coordinated entry list and relying either on social worker referrals or unverified self-reports. The lions share of individuals housed under housing authorities homeless preference models would not have qualified to be counted as homeless on the PIT count.

There are supply side answers to some of the homeless crisis, as the report points out. The state needs to remove those barriers and spend a decade prioritizing construction. But those affordable housing units should be linked to a region's homeless service providers to make the greatest impact on homelessness. The report does reinforce the evidence on national best practices. The work of housing the homeless has to flow through analytical models, focusing on the concepts of vulnerability and FUSE scores and evidence based tools. Those measures will make sure that the chronically homeless get the first available placements, and that the associated systems costs of homelessness are reduced. If we spent a decade building affordable housing for the income related homeless populations and developing service intensive Permanent Supportive Housing, especially congregate PSH models, we could make some progress on ending homelessness. To date the entire system has been underfunded, plagued by half-measures, undermined by failures of governments (at all levels) to insist on best practice models, and plagued by the bad practice of leaving housing decisions to service providers.

Lastly, there is a shelter crisis in Oregon. Not only do we have the second largest unsheltered population in the United States, but our shelter models are generally geared toward lower needs clients without addictions and mental health barriers. Shelters are an incredibly expensive response to homelessness, and they tend to fall under the "managing but not ending homeless approach." Oregon needs to get serious about funding shelters, but also requiring outcomes of them. Forcing them to work with high barrier clients, even those with active addictions, and holding all of us to account on the exit outcomes.

Exit outcomes? Good idea, but it's pretty hard to hold providers or programs to account when exit outcomes aren't made public, eh, Jimmy?

On a final note, for the first time in three years, MWVCAA completed its single-agency audit on time and without material weaknesses. It's also managed to land former City Councilor Steve McCoid on its Board of Directors. For a recent interview with McCoid, see

here.